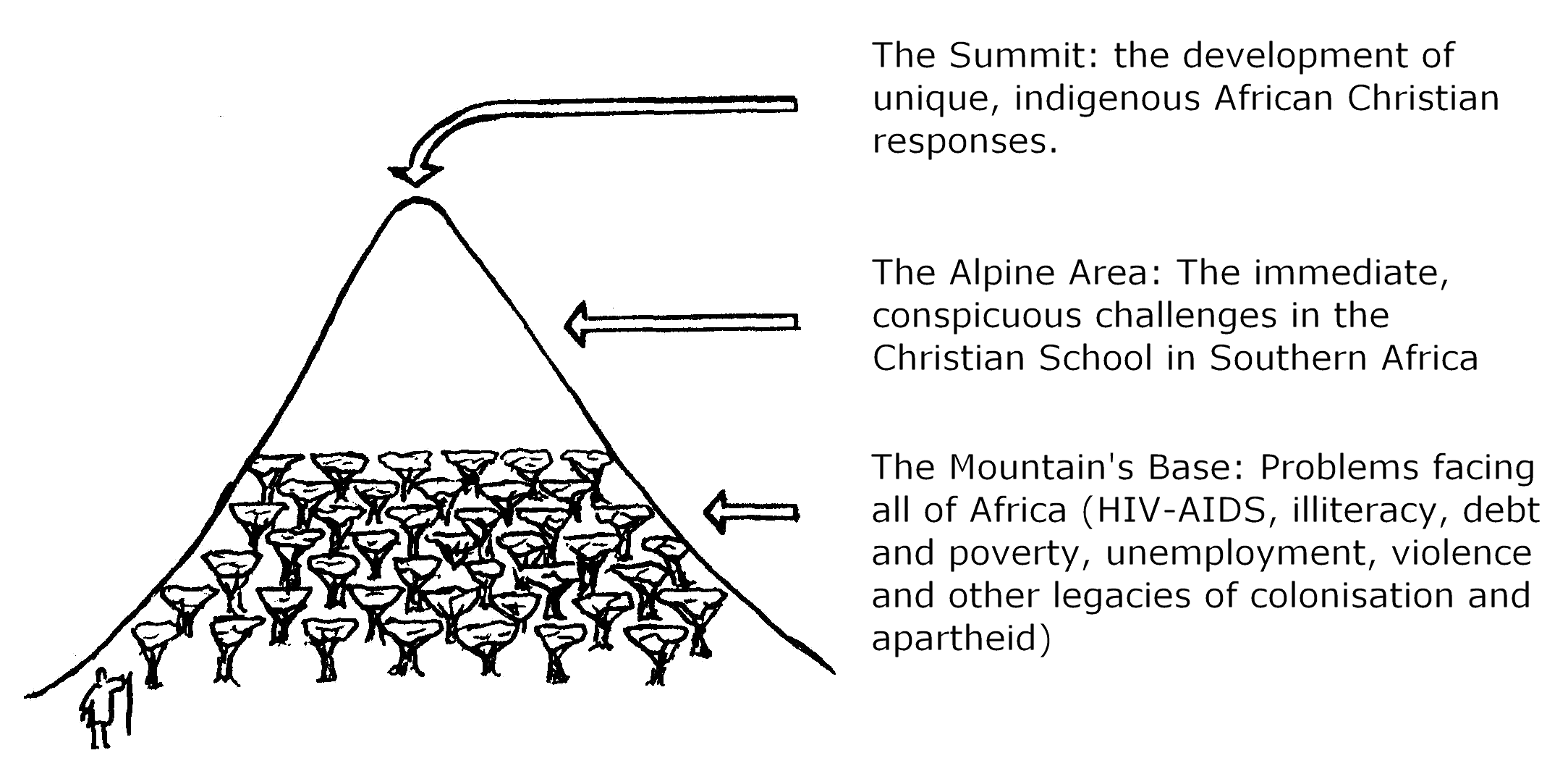

Introduction: The three parts of "the mountain"

We would like to compare the problems facing Christian educators in Southern Africa with hiking over the "mountain" in our drawing below.

Like our hiker, we will start with a consideration of the base and work our way to the summit.

The Mountain's Base: Problems facing all of Africa

The huge problems which impact all Africans are well known: the large percentage of the African population that is estimated already infected with the HIV and the huge toll it will extract from all in terms of grief and social disintegration; the challenge of low rates of literacy that hamper education, communication and awareness of other problems; the massive pressure on African countries that spend up to 60% of their income paying interest for debts to wealthy, western countries and the associated problem of Structural Adjustment Policies that insist that indebted governments spend LESS on education and health care; high levels of unemployment and the eroding of self-esteem that often accompanies it; the multitude of "limiting" legacies of periods of colonisation (and in South Africa, of apartheid) the most important of which is the loss of "confident identity" and an enduring belief that "western" means "superior" (which is also partly attributable to the aggressiveness with which the pseudo-culture of the US displaces all others).

The sheer enormity of these "basal" problems needs wise treatment. Yes, they present LARGE challenges—but that is not to say that these are our ONLY challenges. The fact that they are large means they will require large amounts of our time, energy and resources—but it would be a mistake to extrapolate from this they require ALL our resources! Let me illustrate! Three years ago a very large missions organisation strongly suggested that ALL other considerations be put on hold and that the only problem to be focused on would be the consequences of HIV-AIDS epidemic. They are presently engaged in some excellent work—for example building large orphanages for the orphans that projections estimate will flood the capacity of present orphanages. Buying land, fundraising, commissioning architects and contracting builders is consuming so much of the workers' time that most have had to cut back severely on education, bible studies and evangelism —and in the process the organisation is losing its distinctiveness and witness. In doing so it is voluntarily laying down some of the most effective tools that God has given us to face our challenges. We need to recall the "balance" commended in the Letter of James. Without our foundation, how shall we "critique" the range potential solutions—for instance the suggestion that all is required is the greater availability of condoms?

"Over-embracing" these problems represents one danger - ignoring them, another. To flee from these problems—retreating solely to prayer and spiritual study—is also unscriptural. Again our Christian distinctiveness offers us unique insights to these large problems. The Old Testament has much to say on loans, usury, debt and its cancellation and even more about social justice and responsibility. The 2000 Jubilee recommendations of debt cancellation are examples of movements where Christians should lead—allowing the Gospels light to illuminate otherwise impossible areas.

The Alpine Area: The immediate, conspicuous challenges in the Christian school in southern Africa

Encouraged by James' call to balance, we go further in and higher up.

The lower levels of mountains are often forested. And when you are in the forest it is possible, because of your limited view, to think you are the only person climbing the mountain! Come out into the clear, treeless, snow clad alpine areas and you suddenly see there are many hikers on the same trek as you—facing a similar host of challenges. This is what the All Africa Christian Educators' Conference was like for many African Christian educators! In August 2000, this inaugural conference attracted 700 participants, from 120 schools of 16 African countries. The participants were very encouraged and enthused from being able to share their joys and sorrows with fellow Christian educators and by the workshops. The papers presented were also very relevant to the needs of the participants. A passage from scripture that captured the excitement that many felt at this conference included Mordecai's words to Esther, " And who knows but that you have come ... for such a time as this?" (Esther 4:14)

The common concerns that came out of this conference are what make up the rest of this middle section. Just as the Alpine areas are often conspicuous because of their treeless, snow-clad appearance, so these are the immediate and conspicuous challenges facing many Christian schools in Southern Africa.

- Networking of the existing institutions.

- The training of leadership.

- Teachers' training.

- Development of context-based Christian curriculum.

- Reconciling unhelpful dichotomies (between intellect and practice; between real world and laboratory/classroom; between reason and faith)

1. Networking of the existing institutions.

The All Africa Christian Educators' Conference itself was a great demonstration of the value of networking. Before the conference, the Association of Christian Schools (ACS) was working to network schools, but only around inter-school sporting events. The conference redirected the vision of this Association to see itself as a facilitator for addressing of the challenges that were identified at the conference. The Association of Christian Schools International (ACSI) volunteered to support ACS in this task.

The Association for Christian School is now busy networking the Christian Schools in South Africa; its main goal is to extend this to the whole of Africa. In January 2001 it is planning to open its office in Johannesburg. The administrator will be appointed soon. Once the office is opened, it will address the needs for the schools. Presently the very crucial need for the schools is Christian curriculum. Even in the issue of curriculum something is already underway. What the Association needs is to co¬ordinate the resources. This is also the area where we need international expertise.

Those who attended the IAPCHE (The International Association for Promotion of Christian Education) Conference at Dordt College witnessed the reading and approval of our proposal of starting The Institute for Promotion of Christian Higher Education in Africa. The purpose of this institution is to network the existing institutions in Africa, to promote scholarship in Africa and to work together as a team of Christian educators.

A word of caution is necessary while we are addressing the co-operation with overseas colleagues and networking internationally. Africa's aim here is not to engage in the wholesale importation of ideas and practices. This has been tried in the past! We now understand that this would be counterproductive in the long-term. In the later sections we will discuss further the importance of developing indigenous, African responses to African challenges.

If Christian educators are to develop our own curriculum, we need a very strong network that will enable schools to understand that local curriculum grows out of school community vision. Schools need to be integrated but still maintain their unique local character. Networks need to respect that each school community will have its own history, vision, and purpose of schooling, aims and goals.

2. The training of leadership.

The training of leadership is very important to organisations if they are to continue being a blessing into the future. We can learn much from having observed places in which the leadership has been too narrowly invested in one or two people who are not accountable to others. The danger is that these people who are "lonely-at-the-top" are placed in a very spiritually precarious situation. There is safety in the counsel of many.

Ongoing training of leadership can also help insure the passing of the vision for a school from one generation to another. In the west we have had time enough to observe the secularisation of once¬distinctively-Christian institutions. These schools often bear the names of radical reformers but are now only distinguishable from secular, government schools in terms of the high test scores of their graduating students and the exorbitant fees they charge their parents. Agents of change, which are signs of the Kingdom, can all too easily turn to countersigns of conservatism. Again, as Africans we do not want merely to import western practices—and we certainly don't wish to repeat the mistakes of the west and in a century's time have nominally-Christian schools for Africa's elite.

3. Teachers' training.

We can develop very good Christian schools and Christian curriculum but unless we have trained Christian teachers, the long-term development, growth, change and refinement necessary would doom these schools to being a short-lived experiment. In their final stages of decline there would be teachers who lack conviction because they do not deeply understand the nature of the curriculum they handle. The spectre of the secularised, once-were-Christian educational institutions should be our daily warning!

There are some developments in the area of teachers' training in South Africa. The partnership of the Heidelberg Institute for Christian Higher education in South Africa, the National Institute in Christian Education Australia and the Institute for Christian Studies in Canada is an example of the model that can be followed. This is still happening on a very small scale. It would be helpful if more teachers were involved in Postgraduate programs of this type. Many of our current teaching staff had government secondary schooling and inevitably they hold these as models in their minds. Further, our teachers' training has usually been in secular colleges and universities. They would benefit from being challenged on how to have their Christian faith permeate all aspects of their teaching and on how they link the Bible and education. This postgraduate "challenge" to the way teachers have already been taught to think about education is helpful, but in a sense it is "remedial". Another possibility is for students to be able to choose Christian tertiary education in the first place.

The process is already underway at a Christian University in Port Elisabeth, The Kings University. This is an opportunity that needs to be supported. It is also important that these institutes realise that they are not to be copies of British and American Christian universities. The African Christian universities will need to be distinctively African—not with tokenistic departments of African Studies—but where each department or faculty teaches from a distinctively African perspective as well. A good illustration of this would be that their history department would not ONLY describe the well-trodden historic paths that lead to the Western Enlightenment, Renaissance, Protestant Reformation, Industrial and Information Revolutions. Andrew F Walls, in discussing the necessity for distinctive theological scholarship in Africa, writes,

There has been a tendency to adopt the Western syllabus and then add African (or Asian) church history to it, so that it becomes an appendix to someone else's history, not something that flows naturally out of the Acts of the Apostles. The curious thing is that the aspect of the Western church history which is perhaps is of most relevance in Africa—that period in which the tribal peoples of northern Europe became Christian, and adopted Christianity into their customary law—is rarely studied in depth, even in the West, while the Reformation, which is in comparison a little local difficulty, absorbs immense resources. (It is idle to pretend that Africans are Lutheran or Baptist or Anglicans for the same reason as Europeans or Americans are.) (Walls, 2000)

4. Development of context-based Christian curriculum.

One of the reasons for the importance of distinctive African Christian teacher training is the development of distinctive African Christian curriculum. As Walls succinctly expresses it,

... [The] typical syllabus and characteristic methods of the Western academy do not represent some "world standard" which is forever to be determined by its premiere institutions. (Walls, 2000)

Sometimes changes to curriculum are not initiated by our schools. They are directives from our state governments and we must respond to them as best we can. Sometimes we welcome these changes because, as you will see in the next example, they open to us new opportunities to have more input into the curriculum. The ministry of education in South Africa has initiated a very drastic change - change from the old apartheid system (characterised by rote learning and exams) to outcome-based education or OBE (known in some other counties as 'competency-based learning'). This new system emphasises "learning" above "teaching", and continuous assessment over terminal exams! The new system assesses more than merely the students' ability to "recall" information—it also assesses skill development, attitude and higher-levels of cognitive ability.

The decision of the government to introduce OBE poses some good questions for our Christian educators. Firstly, they need to see that the system is not neutral—it is born out of an educational philosophy. The task for Christian educators is to critique this philosophy, not just to blindly follow.

The philosophy behind the old South Africa system was apartheid and the philosophy of the new system of education owes much to the western concept of democracy, egalitarianism, humanism and empiricism. This system is developed from the thinking of Francis Bacon, the father of enlightenment, who told his followers to forget about speculation of the meaning and purpose of things (teleology) and simply pursue facts. His point was that facts give power. (Greene, 1999, p115) As we shall explore further later, Kant and Descartes have also influenced the thinking of the post- Enlightenment west with the division of the world into the realms of reason and faith. The system also follows John Dewey, who concluded that there is no such thing as absolute truth. He held that we make the truth by using the scientific method and that if it works our truth is reliable.

The system's design is influenced by the philosophy of progressive, learner-centred education. It stops at the child without asking, who is the child? Where is he/she are coming from? Where are they going?

One serious problem with our new curriculum is that it does not develop pupils in a holistic way. If one analyses it carefully you will find that (apart from the first three!) many of the following different ways of knowing are not captured: the logical, the technical, the economic, the spatial, the bodily kinaesthetic, the interpersonal, the aesthetic, the ethical and spiritual.

The positive side of OBE is that it allows for curriculum tailored to local requirements. There are different kinds of outcomes-based education. They differ as to how outcomes are designed, specified and assessed. However, the principle feature common to all outcomes-based education is a distinction between inputs and outputs. Outputs (also described as standards) are centrally designed and prescribed, while inputs are discretionary, and generated and managed locally. Inputs include what teachers and learners bring to learning, indigenous particularities and priorities, textbooks, management and support systems. Since these vary across learning contexts, the key input of what is taught and how it is taught should be as non-prescriptive as possible. Quality is defined and assessed solely in terms of outputs.

The new system allows educators to develop the gifs of an individual child without the distraction and interruption (!) of rushing to examinations or completing their folders. The OBE approach allows the teacher to provide an environment in which every way of knowing is valued. We can help pupils to unfold their individual potential as they use God's gifts and relate to those around them. The OBE has allowed us to build in what we consider an essential ingredient of our task: that students unwrap their gifts as they learn. Pupils learn to use internal and external gifts not only for the personal growth, but also to enrich the school community. One further aim of engaging curriculum is that it should create an opportunities for students to be actively involved in problem-solving initiatives involving critical thinking and creative action in the students' life context.

To achieve the vision of the Christian schools curriculum it requires a definitive interpretation and enriching of National outcomes using our own Bible-based, Christ-centred and African perspective.

5. Reconciling unhelpful dichotomies (between intellect and practice; between real world and laboratory/classroom; between reason and faith)

Let me give two examples of the type of thing the title is trying to describe.

In a science lesson the teacher asserts that "objects continue to move at a constant velocity unless acted upon by an external force". The student—for the purposes of tests and examinations—will file this information away—but in a cabinet labelled "in the science lab only". In the student's real world they know full-well that in order to keep an object moving you need to keep pushing it—the sofa you move for mother when she is re-designing the lounge room STOPS the moment you stop pushing it. But to satisfy (humour?) teachers and requirements students will create many dichotomies—about a whole range of topics like the weight of air, the nature of "coldness"; the rising of a helium balloon; the existence of air pressure. In many cases what is creating these unhelpful dichotomies is the fact that new "teaching" is not constructed on pre-existing foundations but instead are held as levitating, disconnected, autonomous facts to be committed to memory. Good science teachers know the value of reflecting upon and describing pre-existing student concepts. Often a little healthy demolition work needs to be done before we can establish a firm foundation on which to resume construction.

In the area of African Christianity there are many believers who were converted to Western Christianity (a highly contextualised expression of Christianity that grew on European soil for more than a millennium) while still (quite legitimately) holding their African Worldview. Inconsistencies emerge in time but particularly at significant life moments (for example births, marriages and deaths) where this culturally-specific, imported understanding proves insufficient to deal with the whole of the world as they perceive it. The results can be in people sneaking off to their traditional spiritual advisors—often with a sense of guilt, but feeling that they have no real alternative.

The narrowness of the Western Christianity (and most western worldviews) derives largely from another dichotomy which was intentionally created by the architects of the Enlightenment. The dichotomy was Kant's split of the realm of knowledge into the empirically-observable facts and the areas of faith (which could only be held as private opinion). This dichotomy served a purpose of helping the West escape the worst excesses of superstition and the misuses of church discipline. It allowed those in the west to proceed down a road of great and new medical and technological discoveries. But despite our initial impressions it was not a road to salvation or even to a utopia. The road was still part of this fallen world and it led us past spectres such as "the bomb" and Thalidomide. It did not lead to the "Green Revolution" that would feed Africa—but instead seems to be heading only toward profit-driven genetic-patenting. The Kantian dichotomy has also become our straightjacket. Westerners are effectively prohibited from conspicuously spiritual areas such as miracles and demon-possession. In dealing with neo-paganism, the so-called "New Age" many in the west are only just coming to see the shortcoming of a world-view that has much narrower limits than an open reading of the Gospel would demand.

Sunday-only Churchianity and Christianly-named schools whose main emphasis is career development are just two more symptoms of the ability of man to dichotomise areas that should have coherence. The antidote to many of these dichotomies is a gospel that proclaims a sovereign Christ who has claims over "every square inch" of life - even in Africa!

The Summit: The development of unique, indigenous African, Christian responses

This last point (reconciling unhelpful dichotomies) naturally leads us further in and higher up. You can't really say that you have "climbed" a mountain without going over this very important part—the summit. Each of the areas we have passed so-far point us to the necessity to develop unique, indigenous African Christian responses in all these areas.

Without the development of unique, indigenous African Christian responses we could still train excellent Christian teachers... perfect for export to the UK or US. We could still develop excellent Christian schools... but they would have little enduring effect on transforming or contributing to the African situation.

The gospel does not come to anyone in a cultural vacuum. Rather it is conveyed to us through the written accounts of God's work in the lives of specific people and particular people groups. Likewise Christ comes to us not as a disembodied "cosmic" Christ, but incarnate as a Jewish child born at a particular time. As the gospel spreads to new people groups it therefore requires translation but it never becomes a "distilled" product that can somehow be separate from a cultural context.

The decision of the early Church regarding the new Hellenistic believers is important. They did not ask the Greeks to become Jews in order to receive the Good News. Likewise the West should not be surprised that Africa cannot and should not be Westernised in order to become fully receptive to the gospel. At this point some evangelicals begin throwing around the word "syncretism" as a warning! But the real dangers are that the Gospel will be perceived in a diluted form that changes only the outward appearance, but doesn't "shake to the core".

This is not saying anything particularly new. Since "worldview" became a popular concept in Reformed academic circles we have been given a framework to understand the failure of some of the earlier missionary attempts to transfer culture and gospel together as if they were indivisible or to try to introduce a "distilled" gospel as if could survive detached from any cultural setting.

Just as western people groups were given the opportunity to receive the gospel in a way that transformed their culture, Africa must be given the opportunity to translate the gospel into their own "language" and culture. The patronising attitude of "demonising" all African culture is patently false. All cultures have areas of understanding and areas of blindness. The gospel can be used to evaluate a culture: commending what is good, challenging what needs reform.

Conclusion

Christianity has shifted from being a religion centred primarily in the West to one with its main centres in Africa, Latin America and Asia. These new centres will continue the process of "translation" that accompanied the earlier shifts out of Jerusalem and beyond. This is not to declare "independence" - but as the light of the gospel passes from West to South and East there has to be respect for the need to develop indigenous understandings. Similarly, African Christian schools need to celebrate their unique opportunity for fresh readings of the gospel as it transforms yet another culture. The West can share in this exciting process—not as "givers" only - but as partners who stand to learn as much from the partnership.

We express our confidence in the hope that God will lead us; that we shall respond to the need to develop African Christian schools; that we shall respond to the need to train responsive Christian teachers who can discern the needs of their day; that they (together with the wider school community) will develop indigenous, contextualised, deeply Christian curriculum; that this curriculum will be implemented to prepare students for the large tasks the they face as African Christians.

Bibliography

Green, Albert E. Reclaiming The Future of Christian Education, (ACSI, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1999)

Van der Walt, B.J. A Christian worldview and Christian Higher Education for Africa. (IRS Potchefstroom, 1991)

Walls, Andrew F. "Of Ivory Towers and Ashrams: Some reflections on the theological scholarship in Africa", Journal of African Christian Thought, Vol. 3, no.1, June 2000.

Mr Samson Balanganani Makhado [BA (Hons) (SA); Dip. Ed.; MA (Worldview Studies)] has been active in education in South Africa for some 29 years (the first 20 in public schools, 6 in primary and 14 in secondary). He is presently Principal of Tshikevha Christian School and Chairperson of Independent Schools in the Northern Province. He has served as a lecturer at the University of Venda and has given guest lectures at Dordt College, Trinity Christian College and Calvin College as well as delivering a number of papers at universities and conferences, including the International Conference on Christian Education in Sydney, 1996; Vancouver, 1999; and The Vander Wheele Lecture, Chicago, 1999. He is co-founder of the Association of Christian Education in Venda, now the Association for the Promotion of Christian Education.

Mr Dean Spalding (BSc(Hons)(Melb); Dip. Ed.) has taught in Christian schools in Australia for 11 years. His teaching areas include science, maths, music and horticulture. For the whole of the year 2000 he is on an extended sabbatical leave from Mountain District Christian School (Victoria, Australia) for the purpose of pilgrimage and visiting Christian schools, churches and missions throughout the world (USA, UK, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Israel, Ghana, South Africa, Mauritius). He is currently teaching for one term at Tshikevha Christian School. He is also studying for his Masters of Educational Studies with the National Institute of Christian Education, Australia.

The Journal of African Christian Thought, is a twice-yearly publication of the Akrofi-Christaller Memorial Centre for Mission Research and Applied Theology, Akropong-Akuapem, Ghana, which explores some of the fundamental perspectives, issues and skills required for Christian theology in Africa that is deep, reflective and relevant to the enhancement of Christian life and thought in the present new century